By Nga Do

When Thomas Eric Duncan arrived in Dallas, Texas on September 20th, he was realizing a long-held dream – to be reunited with his fiancée and son, whom he had not seen in 16 years. Duncan lived with them for 8 days, before, on September 28th, being rushed to the hospital, diagnosed with Ebola, and held in quarantine. On October 8th, Duncan passed away alone in his hospital room. He was the first person to die of Ebola in this country.

On September 20th, Thomas Eric Duncan was just one of 1.73 million passengers flying into the United States. Today, he is famous. He is the face of the Ebola “outbreak” in the United States.

With Duncan’s diagnosis and death, Ebola officially came to the United States. With the arrival of this highly contagious, deadly disease has come a good dose of concern, fear, and panic. It is this panic which reminds us of the early days of AIDS.

|

|

In the late 1980s, fear of HIV infection, as well as HIV’s association with stigmatized behaviors such as homosexuality, drug addiction, prostitution, and promiscuity, created a hostile environment for people with HIV and AIDS. The “hysteria” can be summed up in this example, when parents at an elementary school in Queens, New York chose to keep their children home after learning that one child, at one elementary school in one of the five boroughs, was HIV positive. From a 1985 Time article, titled, The New Untouchables:

“There are 946,000 children attending New York City schools, and only one of them — an unidentified second-grader enrolled at an undisclosed school — is known to suffer from acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, the dread disease known as AIDS. But the parents of children at P.S. 63 in Queens, one of the city’s 622 elementary schools, were not taking any chances last week. As the school opened its doors for the fall term, 944 of its 1,100 students stayed home.”

Today, we do not hear about students in the United States staying home from school for fear of contracting HIV. Through the work of dedicated and committed research scientists, we have made immense progress in our ability to treat HIV/AIDS. For those with access to care, HIV is no longer a death sentence, but a chronic disease. With this scientific progress, “AIDS hysteria” has largely abated. But HIV/AIDS is still very much a threat – nationally and globally.

In the United States alone, 25,000 people are newly infected with HIV/AIDS each year, while an estimated 250,000 people were living with HIV in 2013. Worldwide, there were 2.1 million new cases, and 1.5 million people died from AIDS-related illnesses. Overall, since the beginning of the pandemic, almost 78 million people have contracted HIV, and nearly 39 million have died of AIDS-related causes.

Though Ebola is much more contagious than AIDS and kills its victims much more quickly, globally and in Africa, AIDS is taking many more lives. We need to feel the urgency we feel about Ebola, about HIV/AIDS. We need to remember and acknowledge the damage HIV/AIDS still wreaks, and do all that we can to end the pandemic.

Please, join us. Help us realize a world without AIDS.

Recently, AIDS Research Alliance received a donation from one of our longstanding supporters, Richard Bloch. It was made in honor of Barry Greenfield, who had been featured in our 2014 issue of Searchlight. In the Searchlight interview, Barry described what it was like to be gay and sexually active in the early 80s, when AIDS first appeared on the scene, how he learned that he had been infected with HIV, and how he later realized that his ability to live without antiretroviral therapy was the result of a rare gift - he is an “elite controller.”

Richard and Barry have known each other for over 40 years. Here, Richard tells us about his history with AIDS Research Alliance, his friendship with Barry, and why Barry’s story inspired him to give.

|

|

Not a picture of Richard and Barry, but we think it communicates the loyalty that we see in both of these ARA supporters. |

When did you come to ARA?

I have been volunteering with AIDS Research Alliance for close to 20 years—since the early 1990s. I had a friend named Howard Portugais, who was involved in ARA early on. I started volunteering for ARA when the offices were on Beverly Boulevard, in the Liberace Building. That was ARA’s first location.

How do you know Barry?

I’ve known Barry since I came to California. I met him through a mutual friend – John Epstein. It must have been 1970. I moved to Los Angeles from New York because I got a job at the William Morris Agency as an agent. I was an agent for many, many years.

I was once the volunteer of the year at ARA. There was a picture and profile of me in Searchlight. I’m probably the longest running volunteer at ARA.

What inspired you to give in Barry’s honor?

I had dinner with Barry – I went over to his house—about a year ago. It was such a pleasant evening. I’ve always thought Barry was very intelligent and nice, and I’ve been impressed by his commitment to giving back. When I saw the article in Searchlight—I’d been meaning to make a donation—when I saw the article about Barry, I thought, isn’t that wonderful that he’s been helping out all of these years? It was a wonderful tribute to him in Searchlight.

Why do you hope for a cure?

Everybody who has been involved with the epidemic since it first started – I’m 76 years old – I was in my 40s when we first heard about it – we have always felt that, through everything, there eventually would be a cure. Since I’m a gay man, I feel it is very important to find out how we can get rid of this virus.

By Stefanie Homann, Ph.D.

In my last post, you learned about AIDS Research Alliance’s first leukapheresis procedure, and why our research team needs to collect white blood cells in order to advance ARA’s HIV cure research.

Since I wrote my last post, we have performed leukapheresis on several more study volunteers, and I have worked to perfect our process for isolating the resting CD4 T cells, which contain the HIV reservoir, from the white blood cells that we collect from each volunteer.

|

|

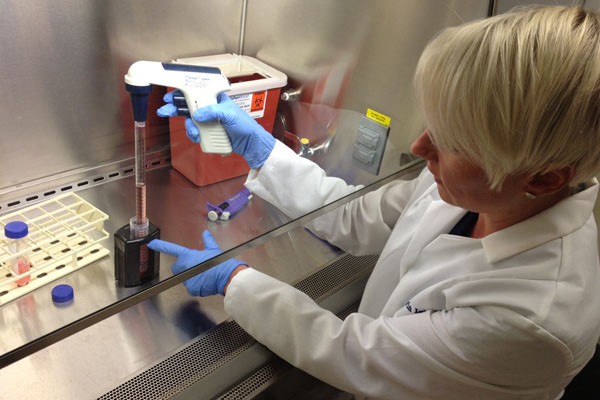

Stefanie transferring the white blood cells taken from our patient to a magnet, which enables her to isolate the resting CD4 T cells from the rest of the solution. |

The HIV reservoir is the barrier to curing HIV. The viral reservoir is “invisible” to the immune system and antiretroviral therapy, so they can’t attack it. But when ART is discontinued, the reservoir can be activated, and the virus will come roaring back if ART is not resumed.

So as researchers working to find a cure for HIV, we at ARA need to focus on the reservoir. But isolating the HIV reservoir is not easy work. Why? Because the reservoir cells are extremely rare. To give you an idea,

To make it all the more complicated, we cannot “see” the reservoir cells; we have to detect them by other means.

So, before we can begin our prostratin research, we must confirm that our research process for isolating the reservoir cells will work.

So far, our process looks to be accurate and effective. I have already extracted the resting CD4 T cells from the leukopak solution. I tested this population of cells, and found it to be 97% pure resting CD4 T cells. Pretty high!

|

|

Stefanie showing us how the magnet attracts the parts of the white blood cell solution that we don’t want to the walls of the test tube, leaving the resting CD4 T cells behind. |

Our next step is to work with the UCLA Virology Core Lab, using their assay in combination with a new assay developed at Robert F. Siliciano’s Lab at Johns Hopkins, to quantify how much virus our reservoir cells produce when stimulated. This way, we can determine which concentrations of prostratin are able to stimulate the reservoir cells in our sample. We will use this information when we conduct our prostratin research to understand how potent prostratin is, and to answer the question—which doses of prostratin induce the reservoir cells to produce virus without being harmful to the human body?

Confirming that our systems are working properly and are sensitive enough to detect the small amounts of virus produced by the rare reservoir cells is no easy thing. But with the help of our collaborators, our research volunteers, and you, our community, we are moving closer to our goal – HIV cure research that could change the course of 35 million lives, and more.

If you have any questions about our work, please contact our team anytime at communications@aidsresearch.org

Thank you for your continued support,

|

|

Stefanie